If the past 14 months have taught us anything, it’s the importance of an organization’s ability to respond to a crisis. While most aren’t as severe as a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic, organizations face adversity regularly. During those challenging times, it’s incumbent upon an organization’s leaders to take charge and guide their teams through the turbulence.

While the ability to handle adversity is essential in many occupations, few vocations face existential threats with the frequency and severity of those in the armed forces. So, to help organizational leaders understand what they need to do during a crisis, we brought in the big guns (so to speak). Chris “Flounder” Earl, Keri Gonzales, and Jim “Tango” Gray from Check-6 — a firm that leverages its extensive military experience to help organizations improve human performance — recently joined our Risk Management Webinar series to present on Leading Through Crisis.

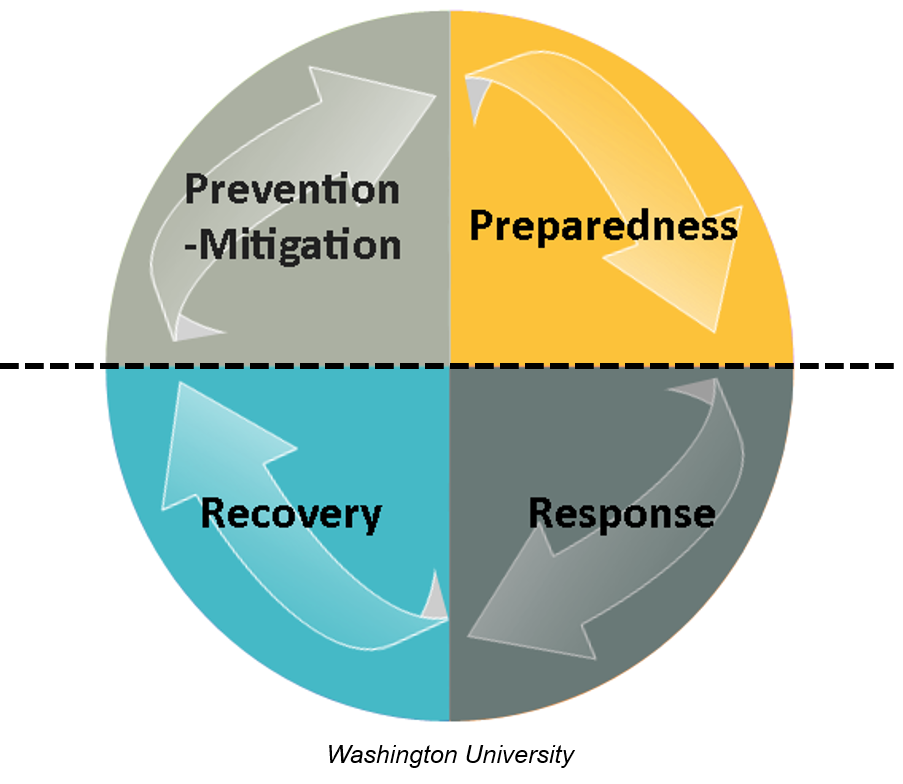

The Check-6 team highlighted four stages that leaders should be aware of when it comes to crisis management (see the graphic below). While all four stages are essential, the team focused on the two phases below the black line to help leaders respond after a crisis strikes. With that in mind, this recap will focus on those stages.

The response stage focuses on the actions leaders take during a crisis to save lives and preserve property. This stage occurs immediately before, during, and after an incident.

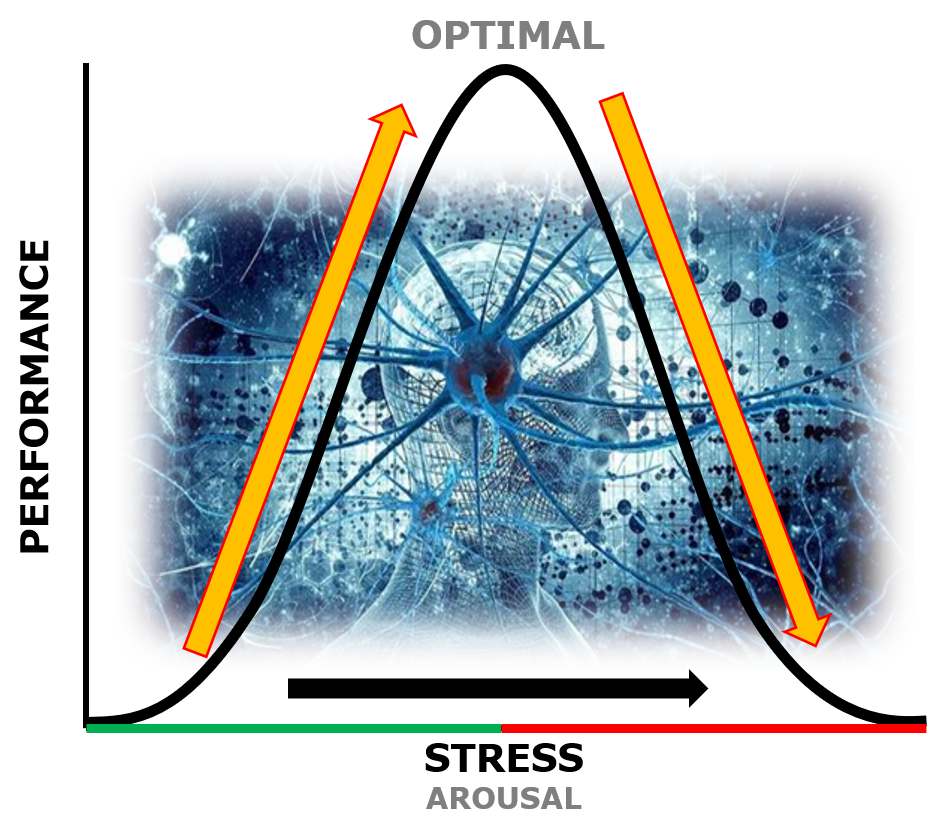

The Check-6 team highlighted the impact that stress plays on an individual’s performance during this stage.

“As we start to get stressed, our performance goes up at first," said Flounder (Earl). “But, too much stress, and we see the performance start to go down.”

According to Flounder, we see this performance curve play out in myriad scenarios. Take, for example, an all-star caliber baseball player who hits well above .300 in low-stress situations but regularly strikes out when the game is on the line. Alternatively, some individuals thrive under that pressure, like the .250 hitter who comes up big in the late innings of close games with runners on base. These individuals have what Flounder referred to as the “It” factor.

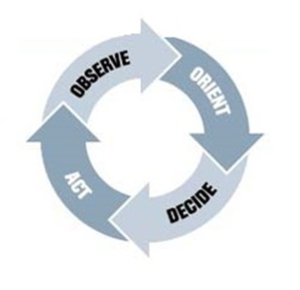

During a crisis, organizational leaders need to harness that stress and not let it diminish their performance. It’s tough to imagine many fields that handle as much stress — and where the ability to manage it is more important — than the military. With that in mind, the Check-6 team recommended a standard military process called the “OODA Loop” to help organizational leaders respond to stress.

OODA stands for:

Following this process allows leaders to stay focused on the task at hand, minimize stress, and help their teams recover from a crisis.

The recovery stage centers on returning systems and activities to normal. The Check-6 team highlighted four considerations to help organizational leaders guide their teams through the recovery phase.

In military parlance, a battle rhythm is a “deliberate daily cycle of command, staff, and unit activities intended to synchronize current and future operations.” Organizations who adopt this rhythm benefit from a more strategic routine and the ability to process information quicker, all of which lead to a faster OODA Loop.

Leaders need to remain calm and stay focused on the task at hand to ensure their team can execute with the added levels of stress inherent in most crises.

“Calm is contagious, and so is chaos,” said Flounder.

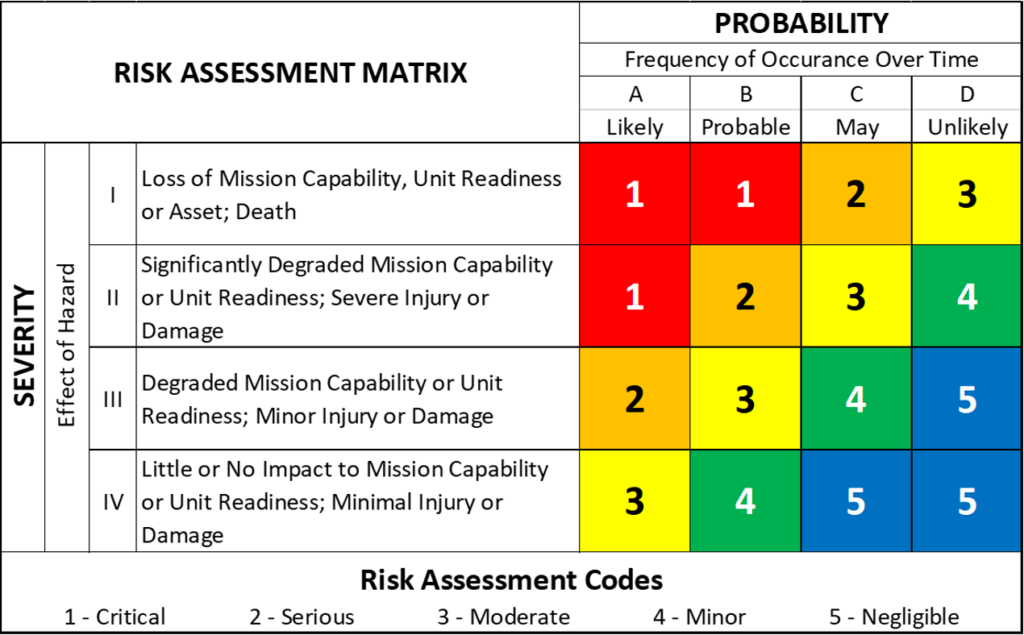

A major component of staying calm is organizing and prioritizing tasks. Flounder shared an example of a risk assessment matrix to help leaders assess threats and prioritize efforts to achieve recovery.

The problem with matrices like the one above is that often in a crisis, every hazard can seem like a Level 1 threat; and, when everything is a priority, nothing is a priority. In these times, leaders must focus on what's essential, triage threats based on their operational impacts, and simplify tasks for their teams. Flounder offered three facets for leaders to identify during a crisis to keep things simple:

With more than two decades of experience as a Royal Marines Commando, Tango (Gray) has intimate knowledge of what makes a command structure effective during high-stress situations. According to Tango, it’s better to have a decentralized command structure than a centralized one with a single person in charge of everything.

“One of the problems of a centralized command structure is as a leader, you become a single point of human failure,” said Tango.

A decentralized command structure allows leaders to delegate responsibilities to their teams. For leaders, it’s about explaining the objectives you want to achieve, then getting out of the way.

The Check-6 team highlighted a few key components of a decentralized command:

While it might be missing from the crisis management cycle above, debriefing is an essential undertaking for leaders after a crisis. Examining team performance (good or bad) during a crisis allows leaders to reflect and learn from successes and failures to improve continuously. The Check-6 teams offered up some questions that are essential to answer for a successful debrief:

Toward the end of their presentation, the Check-6 team stressed how important it is for leaders to take charge during times of crisis. In times of stress, inaction is not an option; leaders need to lead, no matter what challenges they face. The team shared a quote from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that sums this theme up perfectly:

This presentation was part of CRI’s Risk Control Webinar Series — weekly installments of webinars to educate the group captive members we work with on topics like workplace safety, organizational leadership, and company performance. The thoughts and opinions expressed in these webinars are those of the presenters and do not necessarily reflect CRI’s positions on any of the above topics.