Leading an organization's safety efforts is no small task. It requires a leader with proficient communication skills, solid management abilities, and a calm demeanor in high-stress situations. Safety leaders are the ones who have to respond to serious workplace incidents and confront the responsible parties afterward. Navigating the postmortem phase of an accident requires an assertive yet delicate touch to address problems without escalating the situation.

Or, as Caterpillar's Justin Ganschow puts it: It requires a safety advocate rather than a safety cop.

Captive Resources (CRI) recently invited Ganschow to share his expertise on the topic as a member of Caterpillar Safety Services for our weekly Risk Control Webinar series. Ganschow’s presentation focused on helping safety leaders understand what it takes to become compassionate safety advocates when addressing employees after workplace accidents. Here is a recap of his presentation.

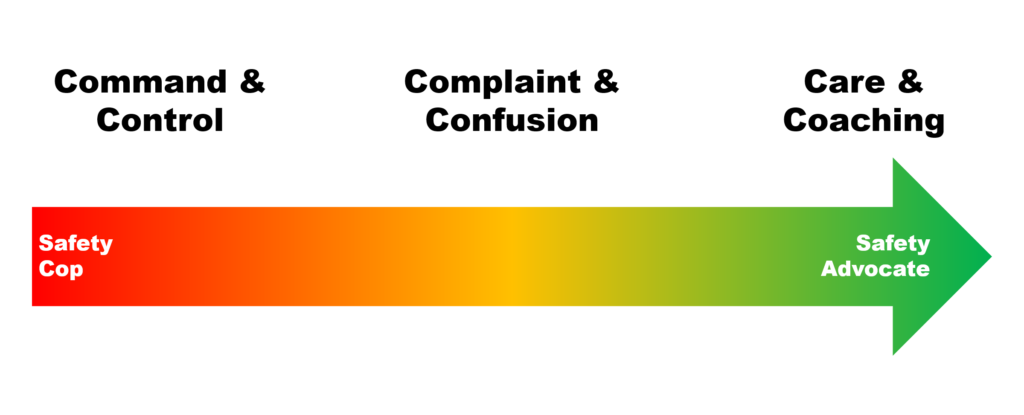

Ganschow set the stage by explaining the spectrum of behavior that safety leaders often land on. The spectrum ranges from a "Command and Control" approach (safety cop) to a "Care and Coaching" approach (safety advocate). The goal for safety leaders, according to Ganschow, is to work your way towards the latter end of the spectrum.

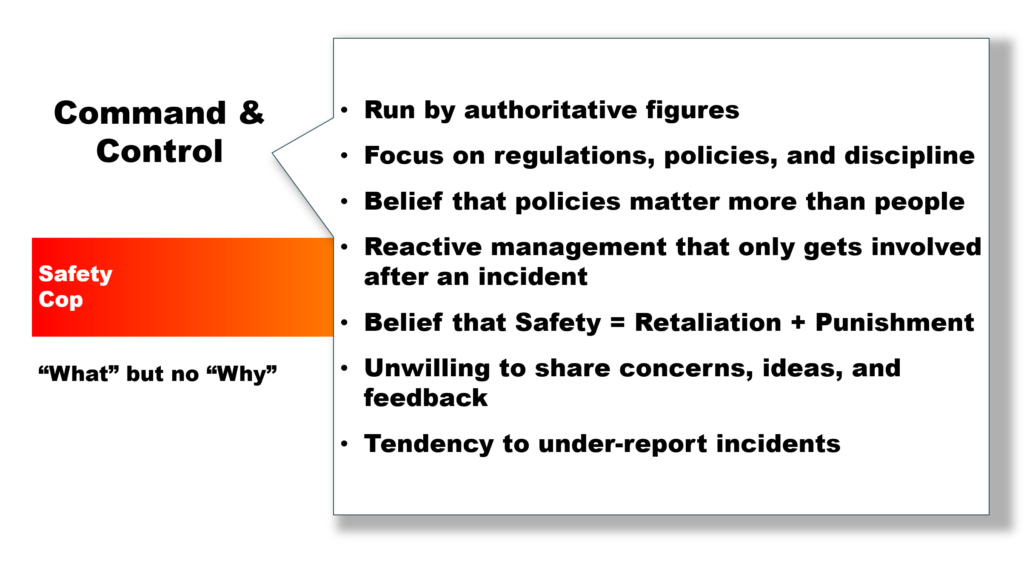

"Command and Control" is the presiding motto for safety leaders on the safety cop end of the spectrum. According to Ganschow, this style of safety leadership is marked by traits like:

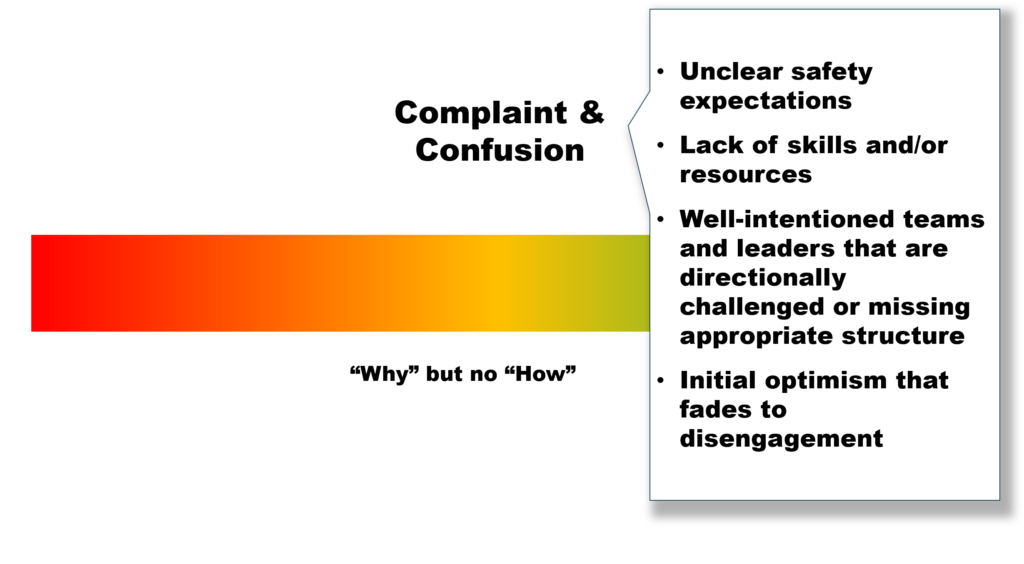

The middle zone of safety leadership is governed by "Complaint and Confusion." Safety leaders operating in this region are more evolved than the previous group, but they still oversee environments with characteristics like:

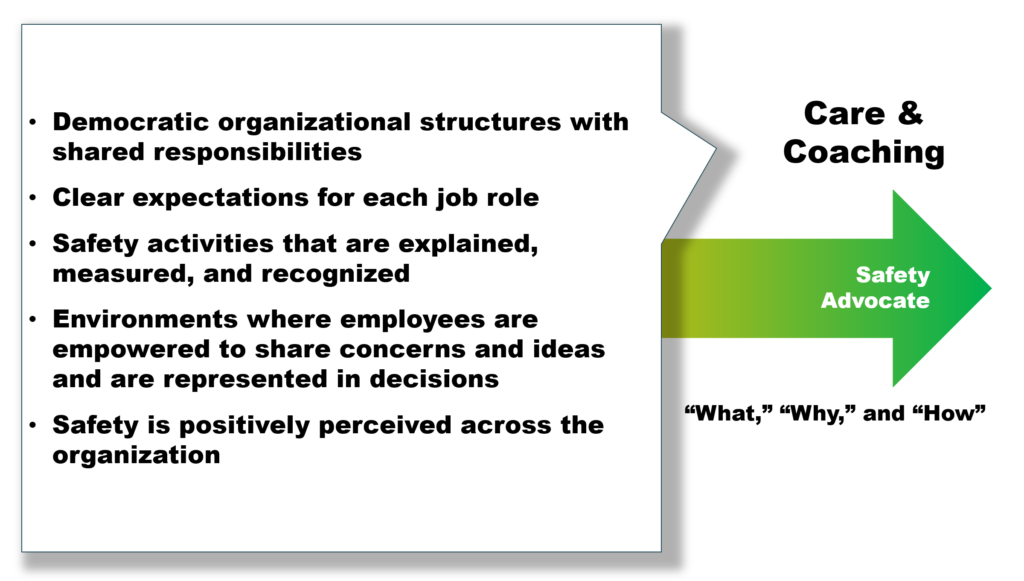

On the farthest end of the spectrum, safety advocates leverage "Care and Coaching" to run their teams.

"These leaders are viewed as helpful, caring, intentional, action-oriented, and cooperative," said Ganschow. "And, importantly, they're supportive."

According to Ganschow, organizations led by these types of safety leaders are likely to possess desirable qualities like:

When confronted, our instinct is to react in one of two ways: fight or flight. This behavior is governed by the primal areas of our brain responsible for survival instincts. When we respond with our primal brain, we're likely to exhibit either an aggressive response (fight) or a passive response (flight).

As a safety leader, your goal should be to confront employees about an incident or risky behavior without invoking either primal response. When we respond aggressively, we tend to escalate situations by attacking the stimulus — i.e., the colleague involved in the incident. When we react passively, we tend to avoid conflict and downplay the incident's significance — leading to a higher chance of it happening again.

So, rather than letting the primal brain run the show, safety leaders should respond assertively and engage in an active and open discussion about the importance of safety protocols.

Now that we've covered the right mentality for responding to workplace accidents, it's important to cover the correct way to communicate with team members. According to Ganschow, successfully addressing an employee after a safety incident is less about the words you use and more about your non-verbal cues during the conversation.

According to studies, communication is:

Ganschow offered advice on how safety leaders can nail all three of those facets of communication.

Handling delicate safety incidents requires a soft touch. Here are a few tips from Ganshow's presentation to make sure your non-verbal cues are assertive without being aggressive:

According to Ganschow, successfully confronting someone about a safety issue is less about what you say than how you say it. Here are some tips to make sure you maintain the right voice and tone:

You've heard the old saying that "sticks and stones can break bones, but words will never hurt," right? Well, leave that on the playground. In work situations, the words you use matter — this is especially true for safety leaders who have to confront employees after workplace accidents when tensions run high. Here are some tips from Ganschow to make sure you use the right words the next time you're in this situation:

Moving past the fundamentals of communication, Ganschow stressed how important it is to emphasize the "Why" behind safety protocols by citing Simon Sinek's Golden Circle. According to the framework, there are three ways safety leaders can inspire action:

"Safety leaders rarely get to the 'Why,' and we certainly don't start there," said Ganschow. But if leaders can "connect with a person's 'Why' on safety, they won't forget it; it's going to alter their behavior."

And, in the end, being a safety advocate is all about inspiring safer behavior.

This presentation was part of CRI's Risk Control Webinar Series — weekly installments of webinars to educate the group captive members we work with on topics like workplace safety, organizational leadership, and company performance. The thoughts and opinions expressed in these webinars are those of the presenters and do not necessarily reflect CRI's positions on any of the above topics.